Why Bob Dylan is a Storyteller Above Anything Else

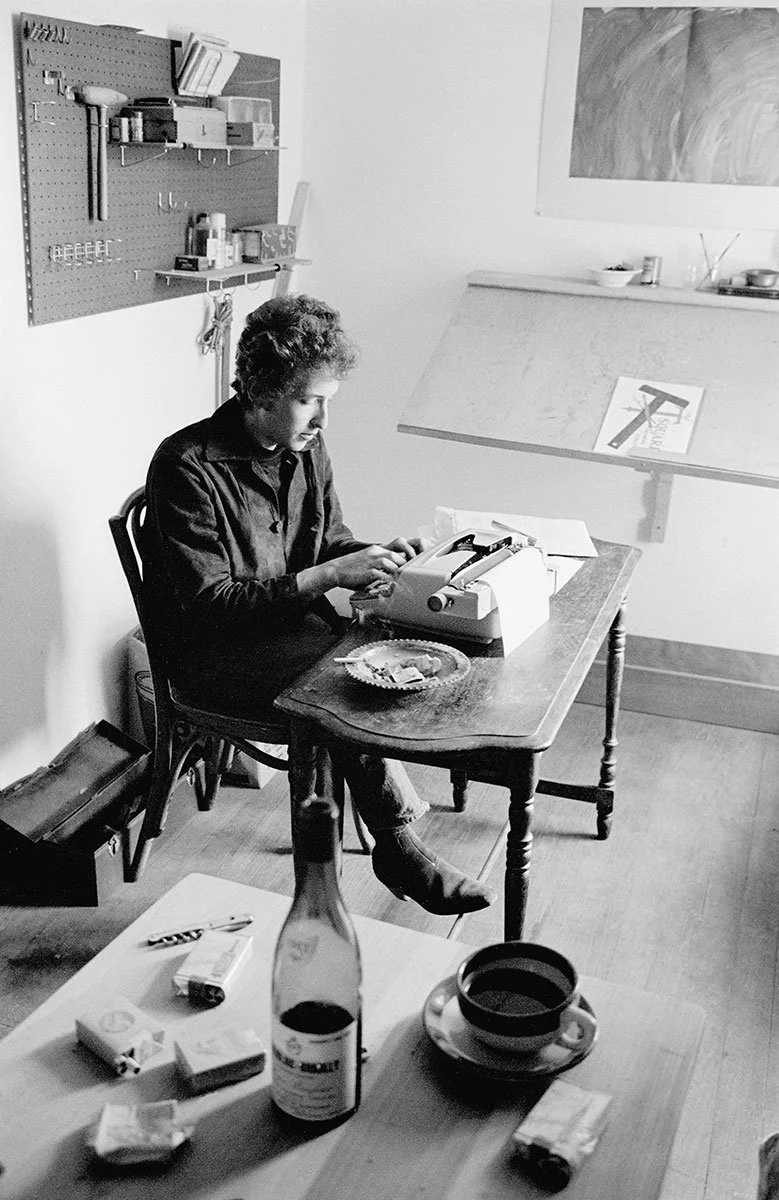

Bob Dylan in writing room above Cafe Espresso, Woodstock, NY, 1964

Photo taken by Douglas Gilbert

This is the second installment in my Bob Dylan phase, and the final research paper I wrote for that Bob Dylan class I took during the fall semester of my senior year at Boston University. I was inspired by the many criticisms I would hear from peers and critics alike regarding Dylan. People expressed disdain for his originality, either saying he plagiarized other artists or that all his songs sounded the same. Others poked fun at his lyrical content; they were of the opinion that all his songs were formulaic in subject matter. I disagreed with these takes right off the bat, and I knew there was something fueling my strident opposition. I poked and pulled at it, and found that it led me to the basic human need for storytelling. Starting with cave paintings, I traced the evolution of storytelling as it progressed from cave paintings, to folk tales, to oral epics, to the development of the concept of intellectual property and creative ownership, to the modern ideas of plagiarism and the increasingly intertwined relationship between art and artist. I came to the understanding that the core component of Bob Dylan’s genius is his commitment to telling a story, weaving together a tapestry of music, poetry, literature, politics, history, philosophy, religion, and conflict to capture the full picture of the trials and tribulations of the human condition.

““Bob is not authentic at all. He’s a plagiarist, and his name and voice are fake. Everything about Bob is a deception.” ”

The above biting criticism of Bob Dylan was expressed by none other than his contemporary Joni Mitchell, in an interview in 2010 with the L.A. Times. Accusations of plagiarism have followed Dylan throughout his career, with derisive takes on his originality, citing his tendency to revive old folk, rock, and blues standards as evidence of his penchant for plagiarism. This is a critique that many artists face. Mitchell’s statement goes a step beyond that and undermines Dylan as a person, calling him inauthentic and “a deception”. Later, in 2013, she would go on to say, in an interview with CBC, that “He’s invented a character to deliver his songs … it’s a mask of sorts.” These accusations, both of plagiarism from general music critics and of inauthenticity and deceptiveness from Mitchell, rely on an agreed-upon framework for ownership of art and the relationship between the art and the artist. However, Dylan’s songwriting and compositions do not fall into this framework. Rather than using his art as a means of portraying his personal, inner truths, Dylan creates his art as a means of storytelling; in this, he carries on the legacy of traditional oral storytelling, dating back to the beginnings of human history. From the era of Classical Antiquity, through the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment, through the Industrial Revolution, till now, storytelling has always been a foundational part of human communication and connectivity. However, modern ideas of artistic ownership and personal expression have created new frameworks within which humans create and tell stories. Dylan, as a modern artist, is subject to these constraints. However, the accusations of plagiarism, inauthenticity, and deception that he has faced are misdirected. Traditional oral storytelling is not about the artist speaking their personal truth, but rather it is about the artist becoming a conduit for the cumulation of lessons and experiences throughout human history. To call Dylan deceptive is to ignore his portrayal of universal truths about the human condition. The richness and expansiveness of Dylan’s historical, literary, and popular culture allegories and allusions cement his standing as a classical storyteller first — songwriter and musician second.

Bob Dylan, outside his Byrdcliffe home, Woodstock, NY, 1968.

Photo taken by Elliott Landy

Traditional oral storytelling was a way to share cultures, moral instruction, lessons, and more, unlike the modern Western perspective of art being a product and, more specifically, a mirror, of the artist. A classical storyteller is an instrument through which stories may flow and evolve, rather than being their sole creator. Ancient humans used storytelling as a tool to record their existence, make sense of the world around them, and bond their communities together. The oldest cave paintings were drawn as long as 44,000 years ago, according to a 2019 study published in the journal Nature. These ancient artists recorded not only their day-to-day reality, but their abstract ideas and beliefs regarding the mysteries of life, nature, and the world. The oral tradition of storytelling is at least as old as these paintings, and cultures all over the world developed their own breed of storytellers. Indigenous people in North America, such as the First Nations, Inuit, and Metis peoples, relied on the oral transmission of stories, histories, lessons, and other knowledge to maintain a historical record, educate younger generations, and sustain their cultures and identities. Ancient Greece had professional storytellers known as rhapsodes, who recited myths, legends, and epic poems. Two such storytellers were Homer and Aesop, whose works are still studied today. Ancient Rome adopted many Greecian myths and transformed them to suit themselves, and thus the Greek stories lived on in Ancient Rome’s storytellers. These storytellers, as well as those of Ancient Greece, were often also singers and musicians, accompanied by a lute or some other musical instrument. As the Roman empire expanded its reach, it encountered other civilizations’ storytellers. Ancient Ireland and Scotland held their storytellers in high esteem; Gaelic society designated different ranks of storytellers: ollaimh (professors), filí (poets), baird (bards), and seanchaithe (historians, storytellers), whose duty it was to know by heart the tales, poems, and history proper to their rank. The Irish filí occupied a role of social importance similar to that of the Bedouin poet in the pre-Islamic Arabian Peninsula and the griots of West Africa. The Bedouin were nomadic tribes, and oral poetry served as a vital means of education, historical recordkeeping, social bonding, and preservation of their cultural heritage. West African griots were singers and skilled instrumentalists, dedicated to preserving the memory of society — speech was believed to have great power in its capacity to recreate history and relationships, and thus the griots were tasked with protecting the history, beliefs, and folklore of West African communities. All of these different storytellers were trained in their art by those who came before them and each culture had its own process for training and preparing its storytellers to take up the mantle. These traditional storytellers from all these different cultures were tasked with learning and memorizing the stories of old, and then portraying them in ways that resonated with their audiences. The word “rhapsode”, according to the Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, means “song-stitcher” (“Rhapsodes”). Generations of storytellers had to preserve the stitching of those that came before them while stitching their own stories and expanding the tapestry of history.

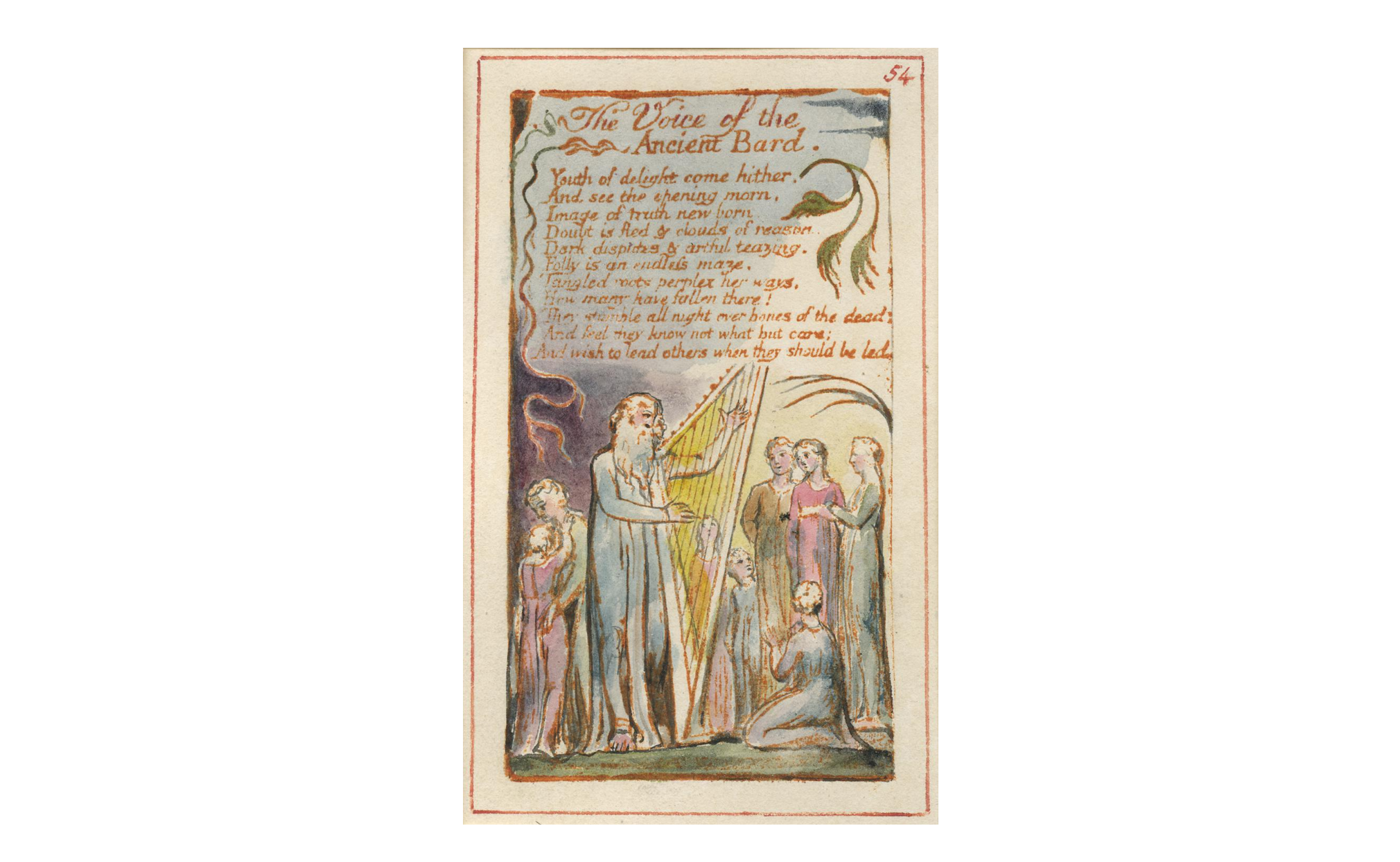

The Voice of the Ancient Bard, a relief etching by William Blake, an English poet, painter, and printmaker, produced in 1789.

Courtesy of The British Museum

Even in the Age of Antiquity, storytellers were influencing and borrowing from each other — Greek myths were adopted and modified by the Romans, the Gaelic storytellers were influenced by the encroachment of Christianity as a result of Roman influence, and so on — without fear of inauthenticity or originality. Now, since the classification of music as fine art, the modern era heavily emphasizes the idea of artistic ownership, creating the grounds for the concept of plagiarism and the existence of copyright law. Music, in a traditional storytelling sense, was used as a tool to engage audiences with a story and aid the storyteller in their incantation. It was a productive form of art; skill was valued over originality. However, as music came to be redefined and understood as fine art, it needed to cultivate certain aspects to make it comparable with other forms of fine art. Philosopher Lydia Goehr, in her 1992 book The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works, claims that this led to the concept of musical “works''. Goehr describes musical works as “objectified expressions of composers that prior to compositional activity did not exist” (Goehr 2). This is a condensed version of the definition she presented in her 1989 article in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, “Being True to the Work”; she originally described works as “the composer’s unique, objectified expression, a public and permanently existing artefact made up of musical elements (typically tones, dynamics, rhythms, harmonies, and timbres)” (Goehr 55). In both her book and “Being True to the Work”, Goehr asserts that the late 1800s was the period in which musical practice — both the creation and subsequent performance of musical works — became regulated by the “beliefs, values, rules, and patterns of behavior and presentation associated with the concept of a musical work”, which Goehr supports with noting the compliance with the score in performances (Goehr 55). Goehr’s identified timeframe has been debated by other musicologists such as David Hunter, who in his review of Goehr’s book for the journal Fontes Artis Musicae asked if Goehr thought that “performers earlier than 1800 failed to comply with score instructions, thereby producing cacophony instead of polyphony?” (Hunter 137). Indeed, the implication that before the late 1800s performers did not adhere to compositional scores seems to contradict the legacy of traditional storytellers undergoing years of training and memorization to faithfully pass on stories in their entirety. However, the exact starting point is inconsequential when assessing the modern understanding of artistic ownership and commodification of music; the outcome is the same. The shift in perception was brought about by multiple factors, chief among these the need to have a musical equivalent of a marketable product to meet the demand of an emerging creative marketplace.

“Within the broad fields of musicology and music criticism, the author remains a central figure both as creative originator and authority. ”

The written word, empowered by the printing press, also contributed to the concept of the ownership of stories. The mass production of printed stories being sold for profit led to writers being held to higher standards of originality. It also led to increased literacy rates and allowed storytellers to distribute their work on a much larger scale, creating much larger audiences and, as a result, more competition amongst storytellers. This, paired with the new concepts of intellectual property and artistic ownership, as well as the Age of Enlightenment’s focus on the importance of individuality, prompted the interest in defining and protecting against plagiarism. In 1755, the word “plagiarism” was included in Samuel Johnson’s dictionary and was defined as: “A thief in literature; one who steals the thoughts or writings of another” (Lynch 4). This cements the concept of creators owning, and thus being intrinsically linked, to their works. Keith Negus, author and professor of musicology, highlighted in his article “Authorship and the Popular Song” the way this concept has become fundamental to our modern understanding of music and, by extension, literature and art as a whole. Negus points out that within musical scholarship and criticism, the author is “a central figure both as creative originator and authority” (Negus 607). In the discussion of music and art, the artists are legally recognized, financially rewarded, and culturally celebrated as the creators of entertainment, literature, music, and art. Building off of this, Negus emphasizes the impact this has on the way audiences engage with art, asserting that “there is considerable evidence to suggest that music listeners interpret and understand songs or symphonies as motivated, authored, and intentionally created” (Negus 607). Negus’s observation sheds light on an extremely important concept for the applications of plagiarism: the idea of intentional creation as a result of an artist’s personal motivation. This binds the artist to their works in a way that did not exist in the days of traditional oral storytelling. Today, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines plagiarism as, "[t]he act or practice of taking someone else's work, idea, etc., and passing it off as one's own" (“Plagiarism”). Under both the original definition and the modern, Bob Dylan does not commit the cardinal sin of taking another’s work for his own. Instead, he incorporates existing narratives into his own as a means of enriching his art by linking it to other stories — ranging from historical, literary, poetic, religious, or musical in nature — from the whole oeuvre of collective human creativity.

“Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.”

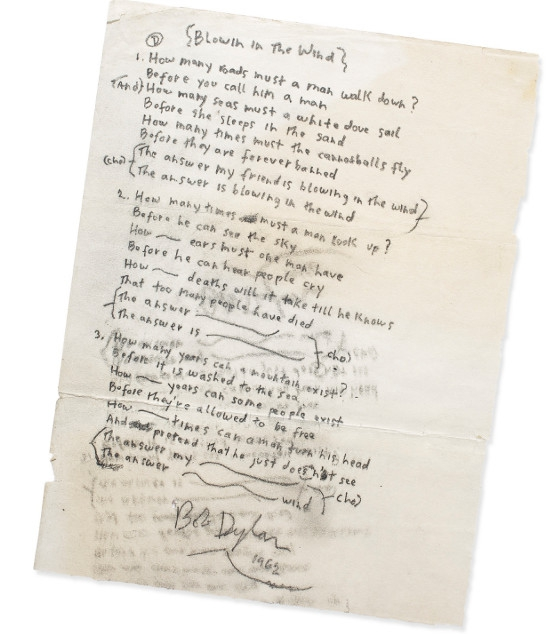

Through the inclusion of references to past historical moments and musical compositions, and his current political climate and popular culture, Dylan follows in the footsteps of traditional oral storytellers by recording his community’s trials and triumphs while placing them in historical context, thus allowing the lessons of history to be aligned side-by-side with the challenges of the present. When Dylan pulled from the musical canon, it was not for lack of original thought, but rather for purposeful layering of meaning to create songs that resonated with not just Dylan’s place in time, but with times before and all the times to come after. The song “Blowin’ in the Wind”, off of his second album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, was an adaptation of the old spiritual “No More Auction Block”, thus transforming “Blowin’ in the Wind” into a modern spiritual song about unshackling the world from war (“How many times must the cannonballs fly / Before they’re forever banned”), tyranny (“How many years can some people exist / Before they’re allowed to be free”), and cynicism (“How many times can a man turn his head / Pretending he just doesn’t see”) (Dylan 5-6, 11-14). The poignancy and power of the song would be lessened without Dylan’s purposeful reference to a past spiritual song. Dylan aligned “Blowin’ in the Wind” with the deep and rich legacy spirituals gained through their place in history. Other songs from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan exemplify Dylan’s purposeful layering within his songs, such as “Bob Dylan’s Dream”, whose melody was based on “Lady Franklin’s Lament”, a traditional folk ballad. The ballad is sung from the perspective of a sailor who is visited in his dreams by the wife of Franklin; she tells the sailor the story of her husband’s failed voyage to the Arctic, and how she would give a fortune to find her husband alive and well. Besides the melody, there are lyrical similarities between “Bob Dylan’s Dream” and “Lady Franklin’s Lament, as Dylan relates his own personal journey to that of Franklin and his wife — like Franklin, he has undergone adventures with groups of friends (''Where we longed for nothin’ and were quite satisfied / Talkin’ and a-jokin’ about the world outside”), only to find himself alone and lost at the end, and like Lady Franklin, he desperately wishes to be reunited with them, no matter the cost (“Ten thousand dollars at the drop of a hat / I’d give it all gladly if our lives could be like that'') (Dylan 11-12, 27-28). The same strategy was used in “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright”, and this song’s melody was based on a song by Paul Clayton, one of Dylan’s contemporaries. Clayton’s song, “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons (When I’m Gone)”, was released three years prior to The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and the two songs, aside from having almost identical melodies, had very similar lyrical phrases. Clayton starts with the phrase “It ain't no use to sit and sigh now, darlin'”, and Dylan starts with the phrase “It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, babe” (Clayton 1; Dylan 1). The third line of both songs is the same, just with different terms of endearment at the end, and both songs include the phrase “I'm walkin' down that long, lonesome road” (Clayton 3; Dylan 3). Despite these similarities, Dylan did not plagiarize Clayton. First, the melody was an arrangement of the traditional folk song “Scarlet Ribbons (For Her Hair)”, which meant it was in the public domain, negating a conflict there. Secondly, Clayton’s lyrics were closely based on the lyrics of a different traditional folk song, “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I’m Gone”, also in the public domain. Both Dylan and Clayton were keeping with the tradition of the collaboration and exchange of ideas, expressions, themes, and phrases in folk music, which is rooted in traditional oral storytelling. Folklorist Carl Lindahl refers to this recycling of content as "floating lyrics" in his 2004 essay “Thrills and Miracles: Legends of Lloyd Chandler". He defines “floating lyrics” within the folk music tradition as "lines that have circulated so long in folk communities that tradition-steeped singers call them instantly to mind and rearrange them constantly, and often unconsciously, to suit their personal and community aesthetics" (Lindahl 152). Dylan built upon what Clayton had written, transforming it into a complex, multilayered expression of the contradictory feelings of a rejected lover: forced apathy, minimization of the pain of heartache, anger, regret, and more, all wrapped up in the pacifying mantra of “Don’t think twice, it’s all right” (Dylan 8).

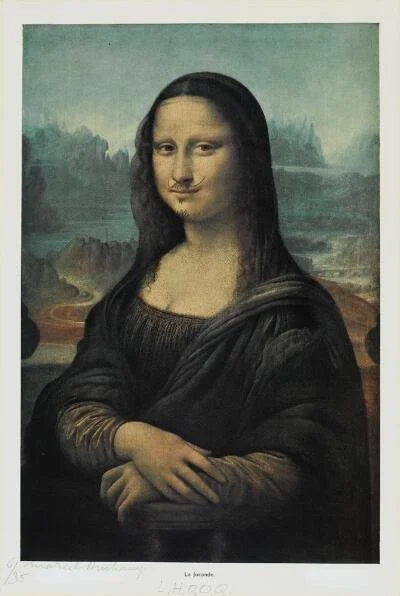

Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q, 1919.

Courtesy of the Norton Simon Museum

“The kernel, the soul — let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances — is plagiarism. For substantially all ideas are second-hand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources.”

Dylan’s expansive knowledge of literature, poetry, and philosophy enables him to reference, quote, and transform pre-existing narratives and cultural images in unexpected and unfamiliar ways, thus calling into question the modern conceptualization of ownership and the limitations it puts upon the creation of new ideas. “Visions of Johanna”, the third song from Blonde on Blonde, showcases the creative power of building upon the works of others, particularly when it is done in a way that presents new perspectives of those previous works. The fourth verse describes a group of women observing the Mona Lisa in a museum, which is reminiscent of the famous phrase from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T.S. Eliot: “In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo” (Eliot 11). The poem is considered one of the most prominent works of the Modernist movement, whose themes emphasized alienation and isolation in the face of modernity. This reference would set a solemn tone — exacerbated by the setting of the museum and the comparison of the museum to a courtroom (“Inside the museums, Infinity goes up on trial”) — but Dylan, in the same verse, calls the women “jelly-faced” and mentions a woman with a mustache who can’t find her knees (Dylan 29, 34). This absurd image undercuts the seriousness of the Eliot and courtroom references. Beyond twisting the tone of the verse and atmosphere of the scene, it also is another reference to a cultural image: Marcel Duchamp’s painting L.H.O.O.Q, which depicts the Mona Lisa adorned by a mustache and goatee-beard. The lines “Hear the one with the mustache say, “Jeez / I can’t find my knees” provide the hint necessary to connect those dots; the Mona Lisa depicts her from the waist up (Dylan 35-36). Duchamp took a cultural icon and reworked it to challenge the accepted perception and understanding of the work, and then Dylan reworked Duchamp. It is particularly significant that this challenging of the accepted beliefs regarding artistic ownership and common perceptions of cultural icons takes place in a museum, a place devoted to enshrining culture and history. By opening the verse with “Inside the museums, Infinity goes up on trial / Voices echo this is what salvation must be like after a while”, Dylan establishes a sense of tension with the trial in the first line, and the ambiguity of what the voices are equating to salvation creates the uncertainty that is necessary for critical examination and questioning of the treatment of art (Dylan 29-30). Art in museums and books in libraries are preserved and protected against the eventual decay brought about by the inevitable passage of time, but they must be deemed worthy to be included; they must be put on trial and found to have a value that will be relevant forever. However, once they are in the museum or library, they are frozen in time, unchanging and untouched. By referencing these works, Dylan pulls them into his creative process and transforms them, expanding the way people perceive these works by using intertextuality and placing them in new contexts. One of the roles of traditional oral storytellers was to keep the old stories alive by building new stories from the foundations the old stories set; Dylan does just that.

“Just like the oral traditional storytellers that came before him, Dylan’s art is made up of a web of threads plucked from the many areas of human creativity, woven into one. ”

"Bad poets borrow, good poets steal," T. S. Eliot is supposed to have said. What he actually said, in an essay on Philip Messinger in his 1920 book The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism, was, "Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different" (Eliot 114). Dylan’s gift that makes him such a compelling, engaging, relatable, ‘good’ poet is that of his penchant for collage. He assimilates, melds, and mixes narratives from across the wide realms of history, literature, religion, philosophy, art, popular culture, music, and human lore to create a multilayered mélange. This is how he crafts his songs; this is how he tells his stories. Walt Whitman said, in a letter to Hellen Keller, “The kernel, the soul — let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances — is plagiarism. For substantially all ideas are second-hand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources” (Twain). That is what the human art of storytelling has been for millennia; all of our stories reflect the sum total of the human condition, as they are all born from the universal themes that bind us together as human beings. In “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” Dylan sings, “he not busy being born is busy dying” (Dylan 11). With this line, Dylan expresses the foundational message that stories, in any form, must be revitalized — or reworked, or renamed, or reviewed — in order to escape decay. The oral traditional storytellers were recordkeepers, historians, and teachers, as well as poets, musicians, and composers. What else is Dylan but a historian when he tells the tragic true story of Hattie Carroll? What else is he but a teacher when he gives advice (“Better stay away from those / That carry around a fire hose”) in “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (Dylan 31-32). Just like the oral traditional storytellers that came before him, Dylan’s art is made up of a web of threads plucked from the many areas of human creativity, woven into one. Just like a rhapsode of old, Dylan stitches together the stories that humans have lived, dreamed, imagined, and created, making his own contribution to the continuing legacy of storytelling.

“[On songwriting] The song was there before me, before I came along. I just sorta came down and I sorta took it down with a pencil that it was all there before I came around. That’s how I feel about it.”