Imitating Bob Dylan's Songwriting Led Me to a Deeper Analysis of "Blood on the Tracks"

Album cover of Blood on the Tracks

Hello, Boxcar readers; Elsa here. Been a while! As we enter into the new year, I hope you’ll stick around as I fully join Zack on the content-creation train. Cheers!

Now, this past fall semester, I took a Bob Dylan class at Boston University. He was my number one artist for my 2021 Spotify Wrapped, and I consumed more Bob Dylan content (songs, interviews, films, documentaries, etc.) in the last four months than I have in all my previous years of life combined. Miraculously, I don’t hate Bob Dylan’s music after this semester! It now feels like listening to the work of an old friend from high school who took a very weird and slightly morally questionable path after leaving our hometown. I’ll explain more later, as I’d like to start 2022 off with a Bob Dylan series of articles (album reviews and soapbox rants, primarily). Hope you all enjoy it, and if you don’t, I’d love to hear why! Disagree with my takes? Hate Bob Dylan? Let me know via our instagram @boxcarcollective or our twitter @bxcrcollective.

This is the first installment of the series. My assignment for the class was to write a song in the specific style of one of Bob Dylan’s albums, and then analyze it from the perspective of a music critic who did not know the song was an imitation; they thought it was a freshly unearthed, never-before-heard Bob Dylan original. I chose to write a song that would have fit in with Blood on the Tracks, an album that has been argued to be Dylan’s greatest of all time (Check out this Rolling Stone reader poll). During this project, I found that by turning the album inside out in order to understand the writing process, I understood the album and the circumstances of the man who wrote it far better than if I had just attempted to analyze the album myself. Imitating the writing of this album, and then critiquing that writing against the rest of the album and analyzing it in relation to the other songs illuminated connections, messages, and themes that make this album, inarguably, a masterpiece.

The lyrics to the song I wrote, which will go by the unofficial title of “Always Lost/Never Found”, is below.

Her fingertips traced lazily

across a blushing sky

tears gleaming upon her cheeks

as the butterflies pass us by

I’m left waiting for final call

as dust settles on the ground

the love we had has flown away

never to be found

They’ve packed their bags and boarded ship

on way to Mexico

Following the sun’s sweet rays

For to survive, they have to go

Champagne breaks and the bottle falls

It’s a sweetly bitter sound

They seek the greenest grass there is

if it can be found

Anne stood atop the battlements

So to watch the trial below

the men argue and debate

if she’s as pure as driven snow

The vote is rigged she knows this now

the power of lust could astound

Life laughs at the punchline o’the joke

hidden and then found

my stomach aches from laughing hard

As the sun sinks and dies

Salt sparkling beneath the light

“But why?” I ask, and she replies,

“We’ve got to hack away the dead,

“rot in our roots is tightly wound,”

Perhaps our love has lost its way

it’s waiting to be found

A phoenix rises from the ash

In’a drought the aloe blooms

Pain ensnares the foolish mind

Despair is the sweetest perfume

The scent, it lingers on her skin

My siren’s song always around

A candle never shines so bright

As when smoke surrounds.

Mist obscures the moon’s pale face

There are no stars to note

A crow cries as he flies ahead

The ferryman readies his boat

I place myself in Antony’s shoes

A damn fool to submit to you

Your lie destroyed an empire

All that was good and true.

(This is the background information and analysis of the album. )

Blood on the Tracks is Dylan’s fifteenth studio album, released in 1975. Over the previous 15 years of his musical career, Dylan had been through multiple distinct eras. He started out as a young, idealistic acoustic folk troubadour, writing tribute songs to Woody Guthrie and political-protest songs for the 60’s counterculture movement. He wrote and performed alongside artists such as the Kingston Trio and Joan Baez.

He left them behind as he entered into his electric, surrealist, visionary folk-rock phase in 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home, wherein he abandoned the simplicity of the traditional folk music scene and the straightforwardness of the political protest songs. He moved away from that psychedelically complex lyrical style with 1969’s Nashville Skyline, transitioning to a brighter, almost country-pop sound as he simultaneously focused on his growing family life; this resulted in simpler lyrics, simpler compositions, and simple sentiments of happiness. He carried this country-crooner vocal styling onto his subsequent album, 1970’s Self Portrait, but it lacked the rustic, charmingly domestic tone of its predecessor and it received overwhelmingly negative reviews from critics and listeners alike.

Dylan’s career took a hit, and although the albums he released from 1970 to 1974 didn’t ever receive the level of critical disdain as Self Portrait, reception continued to be lukewarm compared to the glowing reviews of his earlier works. His reputation undeniably suffered. In early 1974, Dylan embarked on his first tour in eight years alongside The Band. The tour was wildly successful, and both Dylan’s reputation and his wallet were revived; however, the time spent on the road away from his family and deep in the tantalizing rock n’ roll world of groupies, parties, drugs, and alcohol exacerbated the quickly growing tension in his marriage.

Rumors of affairs were reported in the press, and in the summer of 1974, Dylan and his wife, Sara, separated. Dylan then retreated to his farm in Minnesota and wrote what would become the tour de force that is Blood on the Tracks. Dylan initially recorded the entire album over four chaotic days in New York City; then, on the eve of the album’s release, he decided to recall it and re-record half the album. He ended up using three different sets of musicians in two different states, in sessions spread out over three months.

The resulting album is a culmination of all the best parts of Dylan’s past eras -- the earnest, traditional folk singer-songwriter, the poetic visionary speaking in surreal imagery and metaphors, the pointed musical composition of the country rocker, the simplicity and honesty of the open family man — all combine to create a final product that is something beyond an artist simply learning from his past. It is a creation that is greater than the sum of its parts; empowered to be created by a perfect circumstance -- the dissolution of his marriage -- that exposed aspects of Dylan that might have otherwise lain dormant. The album is drenched in pain; aptly titled Blood on the Tracks as it almost seems that Dylan imbued the record with the truth of his anguish, grief, and anger. It is filled with songs of separation, heartache, sorrow, rage and regret. It rails against the inevitability of time moving forward when all you want to do is hold on to the present; it cries out at the pain of tearing yourself apart to try to balance the terrible duality of what we want versus what we need.

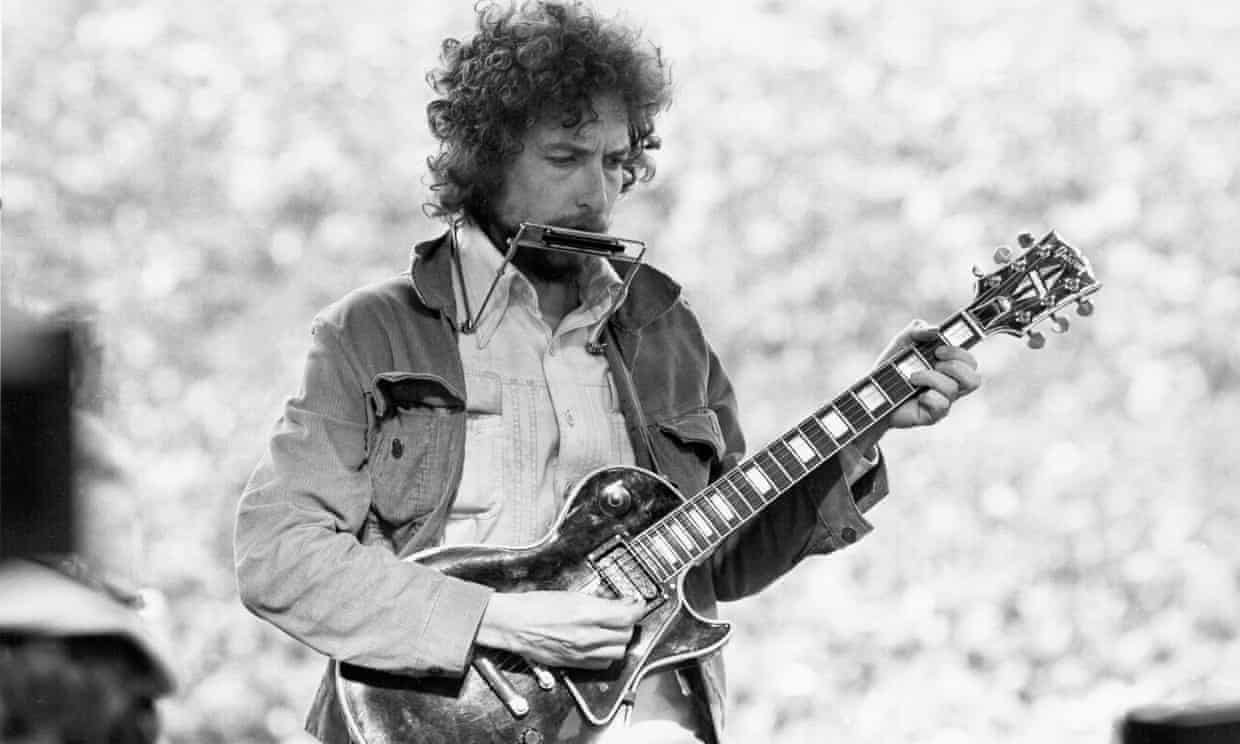

Bob Dylan on stage in a surprise performance at a benefit gig in San Francisco on 23 March 1975, two months after the release of Blood on the Tracks.

Photo taken by Alvan Meyerowitz

The recently uncovered song off of this album, unofficial title “Always Lost/Never Found”, is lyrically written in a familiar Dylan-esque style: an octet stanzaic poem with a loose refrain. The musical composition of the song matches the rest of the album -- open D tuning, capo on second fret, key of E-major. As a result of the capo on the second fret, the song has a brighter feel to it, emphasizing the treble levels of the guitar and Dylan’s voice. Moving the chords up on the neck of the guitar complements the reedy, slightly raspy quality of Dylan’s voice by ensuring it does not get overwhelmed by a lower, bass-rich guitar sound. The song incorporates major, minor, and diminished chords. The song is built around the foundational I - IV - V progression: E-major, A-major, and B-major. However, Dylan adds in the iii, vi, and vii chords: G#-minor, C#-minor, and D#-diminished. The D#-diminished chord increases the feeling of tension (as it is only a half-step away from the root note), only to then make the resolution at the end of the verse even sweeter as the melody finds its way back home to the tonic chord of E-major. The harmonica is overdubbed, allowing for the nasal, whining quality of the sound to stand in contrast to the mid-toned, ambient sound of the guitar. The strumming pattern of Always Lost/Never Found is lightly percussive, emphasizing the bass on the downbeat just enough to keep the rhythm clear. The song is a collage of different stories and scenes, dreamscapes that Dylan describes with typical poignancy and descriptiveness, imparting upon its listeners the uncertainty of love and the fallibility of human nature.

Consistent with other songs on the album, the song effectively demonstrates a confessional, bitter, and contemplative tone. The vignette quality of the discovered song, jumping between storylines and perspectives to convey universal truisms, emphasizes the clear introspection Dylan projects into his songs and enables discussion of the shared conditions of human existence. This album particularly is fueled by the intensity that comes with the dissolution of a marriage. Dylan denied claims that the album is autobiographical; he insisted that the album was inspired by the short stories of Russian author Anton Chekhov. The album may be Chekhovian in its shifting cast of characters and multiple points of view, but there is a deep vein of melancholic contemplation running through songs such as “If You See Her, Say Hello” and “You’re a Big Girl Now”. Their tone suggests a man who realizes what he has lost and is self-aware enough to acknowledge his own flaws that contributed to the mess his marriage became. Lines such as, “Though the bitter taste still lingers on / From the night I tried to make her stay,” and “Time is a jet plane, it moves too fast / Oh, but what a shame if all we've shared can't last,” from the aforementioned songs are regretful admissions of Dylan’s guilt for his failures in regards to Sara and the helplessness he felt watching their marriage crumble. They are intimate confessions from Dylan’s own experience that anyone can relate to; Dylan’s tone of contemplation adds to the universality of the events, emotions, and moments he describes in his songs.

Bob Dylan & Sara Dylan with son Jesse Dylan, Byrdcliffe home, Woodstock, NY, 1968.

Photo taken by Elliott Landy

In “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go”, the lines “Situations have ended sad / Relationships have all been bad/ Mine have been like Verlaine's and Rimbaud's,” were clearly influenced by his breakup with Sara. The reference to Verlaine and Rimbaud, two French poets who had a famously tumultuous, passionate, and ill-fated relationship, and the claim that all relationships are destined to fail illuminates the bitterness hiding beneath the sweetness of the song title’s sentiment. In this new song, there are similar references to famous failed relationships in literature and culture that hint at the disillusionment Dyan feels in regards to love. In the third verse, Dylan jumps to a third-person point of view to describe the trial of Anne Boleyn, beheaded so that her husband could wed one of her ladies-in-waiting, Jane Seymour. “Always Lost/Never Found”, similar to how “Tangled Up In Blue” jumps from first to third person narration, twists from the present to a memory to the future, and throws in references and metaphors galore, containing layers of meaning and emotion. The third verse closes with the line “life laughs at the punchline of the joke,” which betrays the anger Dylan is fueled by and adds to the nihilistic tone of the song and the album overall. In the fourth verse, Dylan describes “salt sparkling beneath the light” after describing a sunset, which seems odd until the rest of the verse is taken into context — the lover is describing “rot in our roots”, and thus the sparkling salt in the fading sunlight is obviously a reference to “salting the earth”. In the Hebrew bible, salt is regularly a symbol of barrenness. One can find other biblical references sprinkled throughout Dylan’s writing; in “Shelter From The Storm”, the lines “I was burned out from exhaustion …/ Poisoned in the bushes …” are also a biblical reference. The use of “burned” and “bushes'' reminds the listener of God’s appearance to Moses in the form of a burning bush. However, the biblical burning bush guided Moses to his divine purpose; the narrator in “Shelter From The Storm” is lost, searching for a way out of his metaphorical poisonous surroundings and into a safe place, ie. salvation.

The Execution of Anna Boleyn, an etching by Jan Luyken, a Dutch poet, illustrator, and engraver, circa 1664-1712.

Courtesy of The British Museum

The musical composition also shapes the tone of the album and this newly discovered song. In this new song, the middle of the verses take a turn with a C#-minor chord, which falls heavily upon the ear, creating a chilly atmosphere. The middle note easily strays off center, souring the sound -- similarly to how the lilting vocal melody will take on twinges of darkness and desperation as Dylan’s voice fries and cracks. As the verse comes to a close, a D#-diminished chord heightens the tension, adding to a sense of yearning for closure as the half-step between D# and E screams for resolution. Dylan stretches the tension out with a quick swoop down to the iii, the G# minor chord, before finally falling into home, at E-major. The unwieldiness of the chord progression creates a haunting tone, which parallels the fraught atmosphere of Dylan’s lyrics.

Consistent with other songs on the album, the song effectively demonstrates the theme that love is not always enough, no matter how desperately we want it to be; the passage of time is the only thing that we can truly count on to be everlasting. The narrator begins by reflecting upon the last time he saw his love, watching a sunrise with tears in her eyes, before she left him, then jumps to the monarch butterfly migration south during the winter in a way that blends the two subjects together. This creates the impression that the woman is similar to those butterflies, fragile and fleeting. The second refrain plays upon the literal evolutionary needs of the butterflies and the old idiom, “the grass is always greener on the other side”. This idiom is a clear demonstration of the fallibility of human nature, but the direct comparison to the butterfly migration implies that humans being unsatisfied with what they have is an unavoidable trait, as ingrained in our DNA as the butterfly’s urge to migrate south.

Dylan’s narrator then switches tracks and jumps back in history to the time of Henry VIII and the trial of Anne Boleyn. The inclusion of the trial of Anne Boleyn, infamously based upon the fickle nature of love and lust, emphasizes the impermanence of love and devotion that Dylan is bitterly raging against throughout this whole album. Armed with background historical context, we know that Henry VIII fell in and out of love, with disastrous consequences for the objects of his affections, many times over his years upon the throne. This is classic Dylan, incorporating literary and historical anecdotes into his lyrics to flesh out the deeper meaning.

This song invokes the natural world as well, with the butterfly migration and the pruning of weeds that is referenced in the fourth stanza. The fourth stanza alludes to the way that love in relationships can become sour, poisoning the entire thing. This kills the flowering love, and as it dies, the scent of rot becomes what one gets used to, as the narrator describes in the fifth stanza, with the lines “Pain ensnares the foolish mind / Despair is the sweetest perfume”. This is a window into the well of sadness Dylan himself has fallen into, and how comfortable one can get wallowing in their own despair, if they so choose.

The song closes with its darkest verse, evoking the Greek myth of Charon, the ferryman of the souls of the dead, and the tragedy of Marc Antony and Cleopatra. Dylan’s narrator sings, “I place myself in Antony’s shoes / A damn fool to submit to you”, and we can assume that he’s not talking about Cleopatra; he’s referring to his lover, the same one who salted the garden wherein their love was growing, the same one who left searching for that greener grass, the one that left our narrator in the dust at the very beginning of the song. The narrator carries on to bitterly rail against the fall of “the empire”, or what we could reasonably interpret as their relationship. The song opens with a sunrise, transitions to a sunset in the middle, and ends with nightfall; these subtle reminders of a day slipping past allude to the inevitability of time, that all things must come to an end. This song is equal parts a warning, a eulogy, a mockery, and a farewell, all wrapped up into one.

Cleopatra and the Dying Mark Anthony by Pompeo Batoni, 1763

Courtesy of the MET Museum

These themes about lost love, the impermanence of love, and the certainty of time are strewn throughout the album in the other songs. Looking at “Lily, Rosemary, and the Jack of Hearts”, references to adultery and betrayal run rampant throughout; in the line, “Rosemary right beside him, steady in her eyes / She was with Big Jim but she was leanin' to the Jack of Hearts,” Rosemary, who was “ tired of playin' the role of Big Jim's wife,” was cheating on her husband, the diamond mine owner, with the Jack of Hearts, the bank robber. In this song, Dylan’s narrative style (which I will expand upon in the next section of the essay) weaves a vibrant yarn of larger-than-life characters treating love and life like a game of cards, flippantly cheating and not taking the consequences of their actions seriously. This is another factor that contributes to the nihilistic and bitter tone I discussed earlier.

It’s also interesting when Dylan’s personal life is taken into context -- he regularly cheated on his wife while on tour with The Band, and then continued to have various affairs thereafter, going so far as to have a girlfriend join him and his kids for breakfast at their family kitchen table. While songs on this album, and this newly discovered song as well, frame the women figures in the songs as the villains, the inclusion of marital infidelity could be Dylan recognizing the part he played in the ruin of his marriage. In “Buckets of Rain” Dylan sings, “Life is sad, life is a bust / All you can do is do what you must”. This reinforces the message that life is not all about love, but rather just making it through.

Consistent with other songs on the album, the song effectively demonstrates a style that is poetic, narrative, unconventional, and rooted in his folk origins. The songs on this album are stories told in and out of time, pieces torn apart and fit back together to create layered images that change depending on which way one observes it from. This is demonstrative of the influence artist Norman Raeben had on Dylan, resulting in Dylan’s non-chronological narrative style, blending the past, present and future all into one to create something that exists beyond the constraints of time. “Tangled Up In Blue”, the opening song on the album and arguably one of Dylan’s most popular, employs a similar style to this newly uncovered song.

Along with the structure and twisting narrative, “Tangled Up In Blue” is also full of passages that conjure a kind of dreamlike reverie, referencing 13th century poems, slavery, revolution, fishing boats, New Orleans, and Shakespeare. While it’s partly a love story about a man and woman meeting—a conventional subject for a song—its use of time throughout the song’s narrative is anything but conventional. It jumps about and lays waste to standard, chronological storytelling. The phrases are rich with imagery and figurative language — lines such as “And glowed like burning coal / Pouring off of every page / Like it was written in my soul from me to you” illustrate the poetic style of Dylan’s songwriting.

In the song “Idiot Wind'', Dylan employs this poetic style along with hints of the surrealist style from Blonde on Blonde; for example, the phrase “There's a lone soldier on the cross / Smoke pourin' out of a boxcar door” is a vividly descriptive illustration of a nightmarish vision. This new song displays the same style, in phrases such as “In’a drought the aloe blooms / Pain ensnares the foolish mind / Despair is the sweetest perfume” and “The power of lust could astound / Life laughs at the punchline o’the joke / hidden and then found”.

It also tells the story of a disintegrating relationship, showcasing Dylan’s narrative style. This is a theme that is seen in the almost 9-minute long ballad “Lily, Rosemary, and the Jack of Hearts”. Musically, Dylan’s stylistic roots in folk shine through in this newly discovered song, with no bass or keys or drums accompaniment, just two guitars and the overdubbed harmonica. The song is based around the I - IV - V progression that Dylan employs in many other songs on this album. That progression only is the foundation on which Dylan then plays around, adding in the relative minor of C#-minor and the chord of dissonant seventh note in the E-major scale: a D#-diminished chord. This carries on with Dylan’s penchant for the unconventional, his habit of playing with the relationships between his chords to evoke certain feelings, moods, and atmospheres in his songs.

I hope you all enjoyed reading this essay and song as much as I enjoyed writing them. Stay tuned for the next installment of the series — it may be a Dylan album review, or the second paper I wrote, wherein I discuss the tradition of oral storytelling, the conceptualization of musical “works”, the ideas of artistic ownership and intellectual property, and how Dylan is a storyteller before he is anything else. Check back soon to find out which!