Contextualizing the Evolution of Black Music from 1980-Present in Ten Songs

An Analytical Compilation By Zack Holden

It's a tall order to try and analyze the evolution of African-American music over the last four decades within the context of just ten songs. In a lot of ways, it feels like a game of Tetris: the puzzle is easily solvable, with a plethora of solutions, but position one piece incorrectly and everything falls apart. Hence, I found that the most logical starting point is to map out the major themes of the period and then find songs that particularly embody the associated movements. (Of course, this also means that there is a certain modularity to the choices, where Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five's "The Message" could have equivalently replaced Afrika Bambaataa's "Planet Rock", Michael Jackson's "Billie Jean" could have replaced Prince's "Little Red Corvette", 2Pac's "Keep Ya Head Up" could have replaced Notorious B.I.G.'s "Juicy", etc.) Starting with the rise and maturation of hip-hop—easily the most difficult movement to unpack—and working filling in the gaps, we can generate a complete synopsis of the period, as follows:

Spurred by the dual hits "Rapper's Delight" (Sugarhill Gang) and "The Breaks" (Kurtis Blow), hip-hop originated as a form of party music in the late seventies cash-strapped South Bronx with heavy influence from a mixture of gang culture, disco, funk, and gay culture. Entering the early eighties and the era of the supreme importance of the "DJ", the pioneering rap trinity of DJ Kool Herc, DJ Grandmaster Flash, and DJ Afrika Bambaataa generated more than just technical innovation. Grandmaster Flash's 1982 single "The Message" articulated the effects of the War on Drugs in Black and Brown communities, instantaneously changing the nature of rap from pure party music to an important vehicle for sociopolitical commentary, while Run-DMC shifted focus from the DJ to the B-Boy with their 1984 self-titled debut, proving hip-hop's commercial viability and concurrently shaping fashion and notions of Black masculinity.

The arrival of Rakim Allah with 1987's seminal Paid in Full brought a new level of intellectualism to the genre. A poet in every sense of the word, Rakim truly built "monuments of monologue that stand the test of time" through intricate rhymes that deviated from the simple ABC pattern of early hip-hop. That same year, Public Enemy emerged on Def Jam with Yo! Bum Rush the Show and placed a stronger emphasis on production, incorporating more diverse background instrumentation and spoken word from Jesse Jackson. Both lyrically and aesthetically, the group promoted the tradition of Black nationalism and Afrocentrism with social, political, and economic consciousness. Thus, it was this biting examination of both the interiority and exteriority of Black life that set in motion the forces behind gangsta rap. With 1988's infamously misogynistic and hedonistic Straight Outta Compton, N.W.A. drew from the centrality of Public Enemy's hardcore attitude to offer a "language of authenticity" about criminal life on the streets of Los Angeles. Soon after, regional affiliations began to develop as the West Coast rose to claim national rap preeminence, carried largely by Death Row Records' towering roster and substantive efforts to widen the accessibility of gangsta rap. Dr. Dre's The Chronic and Snoop Dogg's DoggyStyle sophisticated its production and packaging, while Tupac Shakur's 2pacalypse Now successfully translated poetry and political discourse into the genre. The golden year of hip-hop would come in 1994, particularly noteworthy for Bad Boy Records and the Notorious B.I.G. returning the hip-hop crown to New York with the archetypal Ready to Die.

As a result, the East-West animosity grew deeper and deeper, further fueled by journalists and writers vying for increased magazine sales. Eventually, the conflict turned deadly in 1996 with the dual murders of Tupac and Biggie, and hip-hop officially lost its spirit, its optimism, its innocence. Thankfully, Southern hip-hop materialized out of the ashes as a restorative sinew, reinvigorating the shaken, recoiling genre. Thematically, the "hip-hop South" carved out room to work through the remnants of structural racism and Jim Crow in the post-civil rights era. This was noticeable in the movement's "stank", a modern interpretation of funk (with a little something extra) rooted in a precisely Southern reflection of the sociopolitical climate and lost civil rights premises. It was in this climate that the Atlanta-based OutKast, along with their hometown producers Organized Noize, recognized the importance of using hip-hop as a tool to not only describe and reaffirm their social, political, and cultural experiences as Black southerners, but also experiment with the genre's sonic landscape. For the duo, this often came from eschewing the hip-hop normalcy, evidenced most vividly through the highly experimental, Afrofuturistic ATLiens. Twenty-first century hip-hop kingpins, like Kanye West, Jay-Z, and Kendrick Lamar, would come to draw from this spirit of innovation to further drive its diversification, commoditization, and industrialization, thereby positioning hip-hop as a centerpiece of mainstream popular culture with strong influence on music, fashion, and the visual arts.

During its peak metamorphic years, hip-hop greatly influenced the simultaneous creation of other genres. While working A&R at Uptown Records, Sean "Puff Daddy" Combs specialized in developing hip-hop soul artists who brought the swagger and beats of hip-hop into R&B. His most luminary client was Mary J. Blige, the "Queen of Hip-Hop Soul", whose visionary My Life helped define the genre while providing an introspective glimpse into the pain from her rough childhood, abusive relationship, and battles with addiction and depression. Sisters with Voices (a.k.a. SWV) offered a similar sound, albeit with more emphasis on the "remix" ("...And we had some of the dopest remixes. Nobody could f— with our remixes."), and LaFace Records' co-founders L.A. Reid and Kenneth "Babyface" Edwards thrived on producing other hip-hop soul artists like TLC, Toni Braxton, and Usher. Similar to hip-hop soul, but with added elements of jazz and funk, neo-soul was formulated in large part by Richmond native D'Angelo's 1995 debut Brown Sugar, only to be radicalized and deconstructed on his 2000 sophomore effort Voodoo. Other standout artists like Erykah Badu and Lauryn Hill would offer respective contributions to the genre's development during the late nineties with the formative masterworks Baduizm and The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

Combining hip-hop and dance-pop rhythms with urban contemporary R&B production, Teddy Riley served as the principal architect for "new jack swing". He moved to the Seven Cities region from Harlem in 1990, and according to rapper Magoo (b. Melvin Barcliff), "Teddy Riley made the biggest impact I've ever seen in this area, hands down. Nobody ever moved to this area and affected it in a positive manner the way he did." This is illustrated most palpably through his protégés Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo, who cut their teeth apprenticing with Riley in his Famous Recording studio, eventually working in a production and/or songwriting capacity on a number of hit songs and albums. By the late nineties, the duo had begun to find success as The Neptunes, with a distinctive sound marked by original drum-programming and horn samples. When the band folded in the early 2000s, Pharrell shifted focus, finding his place as one of the most talented and ingenious songwriters of his generation. With an unparalleled, innate understanding of song structure, he brought the bridge back to R&B and in turn defined the neo-soul-based sound of twenty-first century pop music, writing and producing numerous hits for everyone from Jay-Z to Usher to Britney Spears.

Nonetheless, solely focusing on hip-hop and its tributaries ignores the totality of Black music. For instance, gospel entered a renaissance in the late eighties and early nineties after experiencing plummeting sales in the seventies. (From 1972-1978, there were no gospel gold records.) Galvanized by the charismatic Andraé Crouch, this new wave of gospel pushed the traditional form to new heights and new aesthetics. In particular, the genre gained broader appeal through Crouch's various crossover projects, working with everyone from Quincy Jones to Michael Jackson to Prince. Other preeminent shapers of the movement, like the Clark Sisters and the Winans, further broadened gospel's sonic landscape to include elements of secular R&B, soul, and funk while retaining its inherent spirituality. What's more, the Winans' Let My People Go constituted a considerable milestone for the genre in that it was the first Christian record to explicitly denounce South African apatheid, situating the ordeal within the larger historical context of human oppression.

Simultaneously, R&B was experiencing a similar revitalization courtesy of Melvin Lindsey's Quiet Storm radio show. Started while Lindsey was a Howard University student DJ for WHUR, the format featured a more upscale and sophisticated soul sound that leaned heavily on the jazz-infused funk of The O'Jays, Earth, Wind & Fire, and Teddy Pendergrass. Aimed at an older, middle-class suburban, largely Black audience, the show featured music from Anita Baker and Luther Vandross that focused on the interiority of African-American lives. While often erroneously criticized for being a senseless form of escapism, songs played on quiet storm stations were actually designed to provide a calming, soothing break from the rat race of daily life, and as such, the format demonstrated that it is possible for meaningful Black artistic expression to venture beyond the political and righteous.

Withal, a proper discourse of the period is incomplete without considering the triumvirate of pop superstardom: Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, and Prince. At their respective zeniths, they were all ubiquitous, wall-to-wall, inescapable. They served as the paradigm, a living testament to embrace the record and the spirit of improvisation. In one way or another, they all dealt with the trappings and excesses of fame, offering complex cautionary tales. Yet, the three brought unique forms of genius to the table. Michael Jackson was layer upon layer of metaphor. Just like James Brown, he was a vision of ease and grace and energy, both as a dancer and singer, that demonstrated a belief in the one. To that effect, he transformed the understanding of music and the understanding of the one through song and dance, using his body as an instrument, but managed to never sacrifice craftsmanship and attention to detail in songwriting and composition. Prince, on the other hand, was a self-taught musician who embodied the DIY ethos in every sense. Where Michael's ingenuity and intellect stemmed from community, Prince's was much more of the insular, solitary variety. His avant-garde, electrofunk style, the perfect amalgamation of funk, R&B, jazz, and rock, was the product of a singular, unified vision. By contrast, Whitney was closer to Michael: always concerned with genealogy and how people are rooted in community. As a result, she shunned the idea of individual exceptionalism, despite having a single gift. She was (quite literally) born to be a pop singer and eventually groomed by Clive Davis to be a crossover star following the massive commercial success of Thriller and 1999. Fitting the role, Whitney ultimately became a cultural touchstone with her 1991 Super Bowl National Anthem performance, and her influence to this day can be heard everywhere from Top 40 radio hits to the Church pulpit.

Thus, this complex narrative can be contextualized with the following ten songs, with three representing hip-hop, three pop, one R&B, one neo-soul, one funk, and one gospel, and five of which are from the 1980s, three from the 1990s, one from the 2000s, and one from the 2010s:

Record: You Brought the Sunshine | Year of Release: 1980

"You BRought the Sunshine (Into My Life)"

The Clark Sisters

The Clark Sisters redefined the Black female pop vocal sound, serving as a central influence that can be seen in myriad later artists from Beyonce to Missy Elliott. Perhaps most noteworthy were their incredible vocal range and impressive harmonies, in full force on this 1981 crossover hit single from their eponymous full-length You Brought the Sunshine. Much of the song's success can be attributed to lead sister Aberdeena "Twinkie" Clarks' innovative composition, which takes a modernized approach to fortify the traditional gospel sound with synthesizers and snare drums.

Importantly, this cross-pollination with sensibilities from R&B, funk, and soul made the then-dying genre accessible to a whole new generation of listeners, articulated by Twinkie herself:

My mother's work has set a standard but really appeals more to the older generation, speaking to their needs. More and more I feel myself being guided to reach and represent the current generation, to make a musical vocabulary that incorporates the past and makes sense of the present. I know God has given me things for the new album which are completely different from anything we've attempted before, that will touch people who would ordinarily never listen to gospel. And that is our purpose.

Yet, the popularity of "You Brought the Sunshine (Into My Life)" also provides a manifestation of the two-sided disapprovals of the Clark Sisters' evangelicalism: church elders resented the way that the single brought the holy word of God into unsavory bars and discos, while many of those among the "unsaved" took offense to the group's outspoken conservatism.

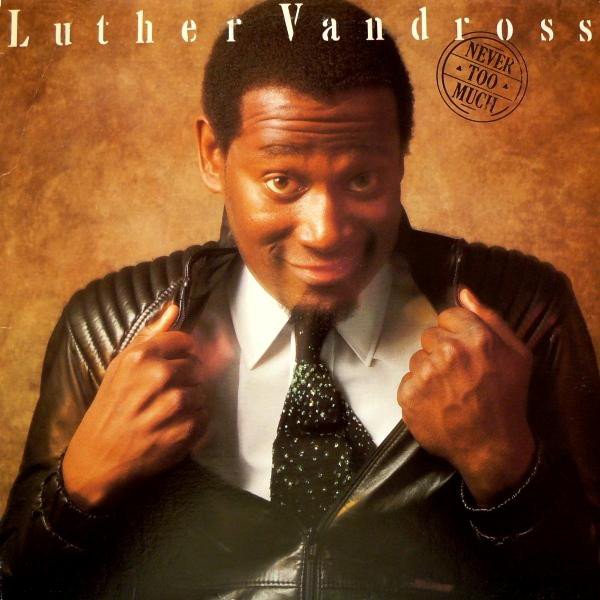

Record: Never Too Much | Year of Release: 1981

"Never Too Much"

Luther Vandross

There is perhaps no other artist who shaped the sound of urban contemporary R&B more than Luther Vandross. Drawing from the warmth and optimism of the Southern soul tradition, one can divulge clear nods to all three architects in his work. Listen to the double platinum-selling "Never Too Much", and you'll find Ray Charles' danceable swing, Sam Cooke's syrupy tenor, and James Brown's assured swagger. Even so, the song is more than just an uninspired facsimile of a long-lost golden age: it signals a new beginning in R&B, a revitalization of the genre for the contemporary era. Stripping away the sixties nostalgia reveals modern production and diversified instrumentation, including strings, bass guitar, and synthesizers, that gracefully infuse the song with pop sensibilities. It is this very commitment to musicianship that would make him a central influence on R&B for decades to come. As John Legend said in the wake of Vandross' 2003 passing, "I'm gonna try to give a hand to Luther Vandross one more time. All us people making slow jams now, we was inspired by the slow jams Luther Vandross was making."

As an originator of the "retronuevo" sound, it's difficult to imagine Kenneth "Babyface" Edwards' neo-soul revolution or Teddy Riley's "new jack swing" movement without the existence of Luther Vandross. Furthermore, these musical crusades drew from another important aspect of Vandross' popularity: his empowering lack of deliberate politicism. By singing purely about love and relationships with a then unheard-of combination of authenticity and sensitivity, Vandross redefined not only the conceptions but also the expectations of what a Black male singer could and couldn't be, gaining scores of both male and female fans in the process. However, even at the peak of his popularity, none of these fans came as the result of crossover success, a striking demonstration of the growing power of the Black middle-class during the eighties and nineties.

Record: Planet Rock: The Album | Year of Release: 1982

"Planet Rock"

Afrika Bambaataa & The Soul Sonic Force

A member of the pioneering rap trinity, DJ Afrika Bambaataa paired with rap group Soul Sonic Force and legendary hip-hop producer Arthur Baker to release the trailblazing "Planet Rock". With a heavily reworked version of Kraftwerk's electronically programmed, synth-laden "Trans-Europe Express" at the rhythmic core, the song set off rap's "electrofunk" period. (Later, this tradition of Afrofuturism would be carried forward by Southern hip-hop masterpieces like OutKast's ATLiens and Missy Elliott's Supa Dupa Fly.) By tapping into the electronic world, Bam blew open the realm of sonic and rhythmic possibilities for not just hip-hop but all dance music, allowing for the creation of beats with faster tempo, higher energy, and hazier intonation.

Naturally, the substantial influence from new wave also meant that "Planet Rock" proved to be pivotal in bringing together the disjointed punk rock and hip-hop crowds, a synthesis that even permeated recordings like the Clash's "Radio Clash" and Blondie's "Rapture". Moreover, taking cues from the punk's architecture, Bam's collaborators the Soul Sonic Force became the first commercial rap group to be conceptualized as a band, rather than a loose troupe of MCs. This would prove to be invaluable for the genre's continued development, particularly during the golden age of hip-hop when rap collectives like N.W.A., Wu-Tang Clan, and Public Enemy emerged who built distinct personalities for their members around an overarching unified sound, demeanor, and credo.

Record: 1999 | Year of Release: 1982

"Little Red Corvette"

Prince

If Purple Rain finally catapulted Prince to pop superstardom, then it was 1999 that first widely demonstrated his ability to create avant-garde, danceable electrofunk. Ever the perfectionist, Prince managed to do the impossible, deftly navigating the fine line between "formulaic" and "artistic". It's easy to discern the painstaking attention-to-detail that went into the instrumental layering on "Little Red Corvette", yet the underlying emotions—optimism, anger, lust—are free-flowing and ebullient rather than cold and calculated. In this way, the song demonstrates a pure mastery of the "Minneapolis sound" he pioneered, a polished hodge-podge of funk, R&B, jazz, and rock that fused Black and White musical tastes.

At a point of continued segregation within the music industry, this universal popularity remarkably allowed "Little Red Corvette" to become only the second video by a Black artist allowed on MTV, behind Michael Jackson's "Thriller". Visually, the video challenged notions regarding not only Black masculinity and sexuality but also Black artistry. Existentially, its airplay on MTV—no matter how begrudgingly granted—challenged conventional notions regarding the place of Black musicians within the industry. Thus, by reaching the stratospheres of pop fame, Prince paved the way for hip-hop to attain broad commercial viability nearly a decade later during its golden age.

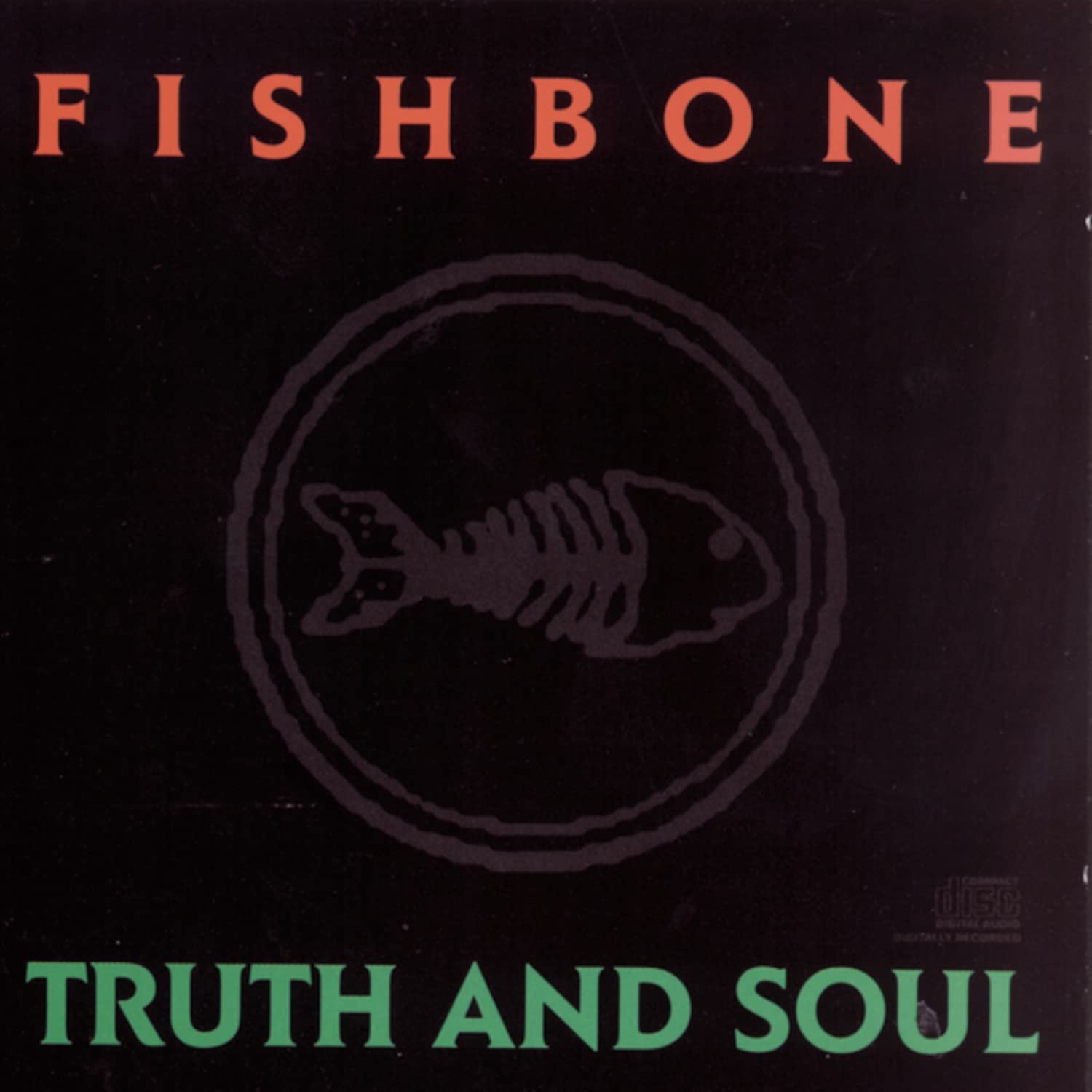

Record: Truth and Soul | Year of Release: 1988

"Freddie's Dead"

Fishbone

Sonically, this song fuses a standard punk architecture with heavy ska and funk undertones, arriving at a unique form of funk modernism that seemingly draws as much inspiration from Deep Purple as George Clinton's Parliament-Funkadelic. Now, while this progressive sound is certainly an interesting topic of conversation in and of itself, perhaps more compelling are its associated visual tangentials. As the group's breakthrough single, the music video for "Freddie's Dead" gained significant airplay on MTV and accordingly brought the "New Black Aesthetic" (NBA) into the widespread national public consciousness.

In his eponymous landmark essay, Trey Ellis defines the NBA as a "post-bourgeois movement driven by a second-generation of middle class" in which cultural education flows from a melting pot of ethnic origins. By appearance, members of the movement sport a polished, intellectual appearance replete with suits, Ghanaian scarves, and small, round glasses. As such, the young twenty-somethings who embody the NBA are easily able to navigate the White world without losing their "soul", thereby demonstrating the existence of a postmodern Black cultural renaissance to the growing neoconservative population.

Record: Ready to Die | Year of Release: 1994

"Juicy"

The Notorious B.I.G.

After launching the careers of hip-hop soul artists Jodeci and Mary J. Blige while working A&R at Uptown Records, Sean "Puff Daddy" Combs was poised to make waves in the industry following his 1993 departure from the imprint, and Christopher Wallace, better known as the Notorious B.I.G., was the perfect artist to serve as the burgeoning Bad Boy Records' flagship. True to form, Biggie's classic 1994 debut Ready to Die not only established Bad Boy as a commercial rap powerhouse, but also proved critical in New York's ascendency back to the top of the regional hip-hop wars. His hard adolescent life as a drug-pusher, penchant for intricate and imaginative storytelling dotted with grim humor, and undeniable MC skills all came together to provide the East's answer to the West's The Chronic.

As a whole, the album is particularly noteworthy in that it represents the tipping point for hip-hop's commercial viability. In particular, "Juicy" employs high-quality G-funk production that softens the hardcore lyrical attack with nostalgic samples and accordingly provides accessibility to a wider cross-generational audience. Thematically, the track is an exploration of both inward and outward growth, celebrating hip-hop not only as a second chance at meaningful, prosperous life for Biggie but also as an evolving, expanding industry. As such, the associated music video offers an excellent glimpse into the clothes, cars, and aesthetic of "ghetto fabulousness", an exhibition of "rags-to-riches" wealth.

Record: Brown Sugar | Year of Release: 1995

"Brown Sugar"

D'Angelo

D'Angelo's lead single "Brown Sugar" dropped in the spring of 1995, right on the heels of hip-hop's golden year. For those who were growing tired of the sampled G-funk beats and steely vocal deliveries dominating the airways, it was a long-awaited return to "real music", reminiscent of soul masters like Al Green and Marvin Gaye. However, D'Angelo's sound, while deeply reminiscent of the Southern soul tradition, incorporates elements of jazz, R&B, funk, and hip-hop to arrive at something altogether different. The controlled, purposeful falsettos are pure Sam Cooke, but the rhythm section distinctly recalls A Tribe Called Quest's laid-back, groove-laden delivery. Celebrated as a high water mark of the '90s, "Brown Sugar" and the album of the same name proved groundbreaking in the development of neo-soul, opening the door for subsequent genre-defining tour de forces from Erykah Badu (Baduizm, 1997) and Lauryn Hill (The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, 1998).

On Brown Sugar, D'Angelo was truly the musician's musician, writing, arranging, and producing all of the tracks himself with a kind of independence unseen since Prince. Accordingly, EMI marketed the album in a specific way. Leaning into his unparalleled talents as a multi-instrumentalist and singer/songwriter, the music video for "Brown Sugar" simply finds the artist serenading a bar full of people while playing the piano, a departure form the glitz and glamor typical of rap videos. Thus, D'Angelo was importantly positioned alongside Teddy Riley and his "new jack swing" as an alternative to the prevailing hip-hop and contemporary R&B of the times, characterized by a commitment of integrity, respect for tradition, and dedication to craft.

Record: Aquemini | Year of Release: 1998

"Rosa Parks"

OutKast

The "hip-hop South'' tangles past, present, and future descriptions of southern Blackness in order to reflect the complex experiences of Black southerners coming of age in the 1980s and 1990s, using hip-hop culture as a means to buffer this generation from the idealistic—and at times unrealistic—expectations of civil rights era Blacks and their predecessors. OutKast served as the "founding theoreticians'' of this sociocultural landscape, with its genesis point coming from André 3000's infamous 1995 Source Awards quote, "The South got something to say." Three years later, the duo dropped Aquemini in the wake of the Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. murders, at a time when the West Coast hip-hop scene was all but dead and the East Coast was tired and overextended, save for southern-collaborator JAY-Z.

In Third Coast, Roni Sarig conjectures that it is this very work that provided southern hip-hop's first masterpiece, both "defining and transcending the genre." On the heels of the highly experimental, Afrofuturistic ATLiens, Aquemini established the duo's combined abilities to explore new sonic boundaries for hip-hop, generate powerful statements of purpose, and combine southern iconography and music with urban pop. All of this is most apparent on "Rosa Parks", the album's most commercially successful—and as it turns out most controversial—track. Beneath the somewhat vague lyricism, one can clearly determine that André and Big Boi still take offense to the South's marginalization in the hip-hop world and hope to finally garner well-earned, yet long-overdue respect from the industry's major players.

Record: Miss E… So Addictive | Year of Release: 2001

"Get Ur Freak On"

Missy Elliott

Timbaland and Missy Elliott secured their standing as some of the most inventive producers of the time with her 1997 debut Supa Dupa Fly, a watershed album for both hip-hop and R&B. After a disappointing sophomore effort in Da Real World, the duo were poised to come back in a big way with 2001's Miss E… So Addictive. More than any other album, it showcased Timbaland's unique ability to extract funk from the unlikeliest sources, like mundane objects or even the human body. To that effect, the lead single "Get Ur Freak On" ushered in the millennial pop era with a "dirty", futuristic sound that only could have come from the new, global South. Rooted in electrofunk driven by Indian tabla percussion and Japanese koto-inspired riffs, the song perfected the experimental production that would permeate Timbaland's future work throughout the decade with everyone from Jay-Z to Justin Timberlake.

In watching the provocative video for "Get Ur Freak On", Missy's importance in bringing a fresh look to both hip-hop and R&B becomes blatantly apparent. Casting aside the "bling-bling" and bravado that sparked the East-West wars and consequent murders of Biggie and Tupac, Missy Elliott reinstated hip-hop's long-lost optimism, saving the genre from its self-dug grave. Visually, this new aesthetic favored Afrofuturism over the long-pedestalized combination of realism and consumerism and manifested in a striking, unmistakable presence that centered dance without objectifying her body. In this way, she demonstrated that there are multiple ways to be Black, to be a woman, to be an artist, to be sexual.

Record: Lemonade | Year of Release: 2016

"Formation"

Beyoncé

In many ways, "Formation" feels like a culmination of the aforementioned movements in African-American music. The grimy electronic beat pays homage to the Afrofuturistic funk that put Missy Elliott and the new, global South on the map. The vocal harmonies, swooning but with a barbed, distinctly urban edge, recall the neo-soul of Lauryn Hill's seminal solo debut. Even the plain, undisguised political messaging about police brutality and the overall state of contemporary Black life in America takes cues from conscious hip-hop artists like The Fugees, Digable Planets, and The Roots. Additionally, the song employs modern feminist and womanist doctrine, in conjunction with personal encounters with relationships and infidelity, to examine questions of Black identity and self-love. Thus, Beyoncé's "Formation" is informed art in the purest sense, drawing from a combination of past tradition and present experience to push the discourse forward.

The timing of the song's release—a mere 24 hours before her scheduled performance at the Super Bowl 50 halftime show—was critical: an unapologetic illustration that the singer could participate in commercial endeavors without losing her ability to offer intelligent social and political commentary. In turn, this luminous coalescence of intuition, vision, and guile illustrated Beyoncé's continued understanding of the importance of exercising her celebrity and ubiquity to explain, in clear and expressive terms, the totality of today's African-American experience, including "standards of beauty, (dis)empowerment, culture and the shared parts of our history." If Whitney Houston was simply "The Voice" and "The Blueprint" for the twentieth century, then Beyoncé is redefining the paradigm for what it means to be a Black female pop superstar in the modern era.